By RUDHYAR D. CHENNEVlERE, New York, March 1919

Amedeo Modigliani: Reclining Nude (c.1919)

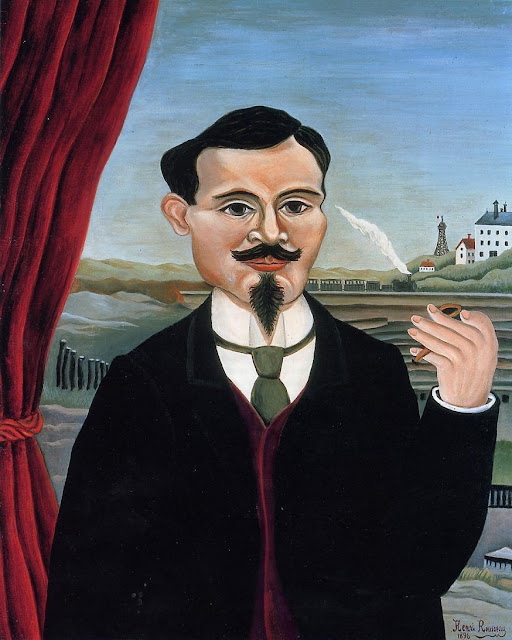

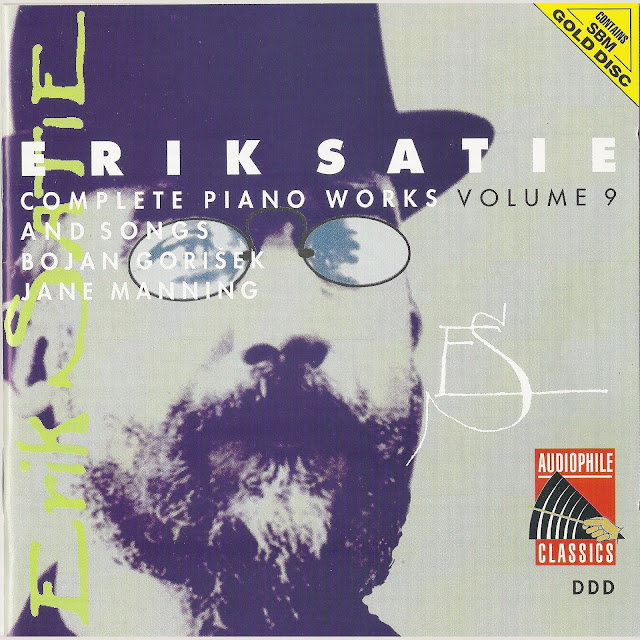

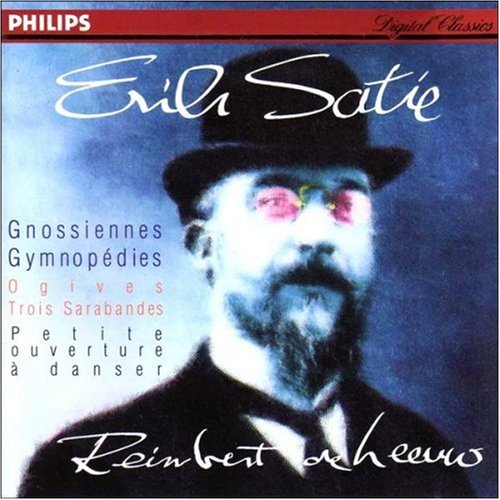

AT a time like the present, when the most contradictory artistic tendencies are confounded in an appalling chaos, in which it is difficult to determine the great subterranean current out of which the future will gush forth, there is a certain interest in detaching a curious musical figure, that of Erik Satie; and of seeking to penetrate, from a historical as well as a purely musical standpoint, the meaning and value of the few works — mainly piano compositions — which he has written. I say "works," though the word is a lofty one to use for the strange, short pieces which Satie — I am considering only the Satie antedating the Parade, his recent ballet, with which I am not acquainted — offers us.

And the expression "musical works" would seem to be even less applicable, since Satie, who from the historic point of view holds an eminent place in the evolution of the language of music, is at bottom as little a musician as it is possible to be.

Some have called Satie an "ironist." And, in truth, the term may be said to apply to him. Yet has irony any musical value? Is not the phrase "the music of irony" absolutely meaningless? It is this fact which I would like to demonstrate here, and thus disengage the notably representative value, in a historical sense, of Erik Satie, who, after having served as the precursor of the Debussyian musical renovation — at least from a formal point of view — has become a "musical ironist," and as such the represent- ative in music of an intellectualism and individualism beyond measure, which has given us the art of these recent years, complex, sterile, as opposed to the profound and essential worth of true Art, whose values are synthetic and mystic, "synanthropic" values, I might say, based on the communion of humanity.

Erik Satie — as we have been informed in a well-considered article by Jules Ecorcheville (S.I.M., 1911), whose noble and untroubled death on the field of battle was a great misfortune for international art — was born in Honfleur, May 17, 1866. His mother was of Scotch descent. He is said to have developed a great fondness for the liturgic chant at an early age, and would listen to it with delight for hours at a time. He studied with but scant success at the Paris Conservatory. And what must have been the spirit controlling this worthy institution at the time, if we are to judge by what it is to-day!

Pablo Picasso

Satie stayed there several years, but the instruction given him seems to have affected him as little as the proverbial water did the duck's back. It cannot be said of him, as has been said, not without justice, of certain others, that his works show he had made up his mind to act in direct opposition to the Conservatory rules, which is only another way of following them. As soon as Satie begins to write (Ogives, 1886 — Sarabandes, 1887 — Gymnopédies, Gnossiennes, 1890), he revels in full liberty, one might even say in full anarchy, in entire originality; and we shall see that all else may be denied him, save and excepted the originality aforementioned.

These initial compositions are slow and solemn successions of seventh and ninth harmonies, indefinitely linked, occasionally yielding place to a processional of majestically perfect chords. Of plan of construction there is not a trace. There seems to be no reason why these chords might not continue for hours.

One senses that their originator has dallied voluptuously with these sonorities, very lovely, unknown at the time and relegated to the index of forbidden dissonances. One feels that for hours at a stretch he has caressed the ivory keys, sounding them softly, then, little by little, with greater force; gloriously, then again more gently, allowing them to die away in ecstasy or satiety (in the latter, alas, only too often, from the listener's standpoint). One feels that the composer's sense of hearing, his nerves, vibrate sensuously, lulled by these infinite undulations of sound.

The Satie of these compositions seems to be a cerebral sensualist. And it is this, rather than the direct influence of plain chant, which has led him to string long rosaries of solemn chords; it is this which has drawn him toward the vague mysticism which with him, as with nearly all those of his own period, was essentially superficial: the neurotic mysticism of a voluptuous woman, transmuting unsatisfied sensuality into cerebral reveries.

It was at the time when neo-mysticism and symbolism gushed forth from the solemn fount of Parsifal. The influence of the English PreRaphaelites had penetrated the youthful artists of France. The Sar Peladan was seeing visions, deciphering the hermetic arcanas of the Chaldean magi. The souls of the cathedrals were being discovered. It was the epoch of long stations in minster naves impregnated with the glow of stained-glass windows of symbolic design.

And its artists were too feeble to create a new mysticism, to lend a divine meaning to life, to think and to adore Eternity in them — to do that which offers itself as the arduous and splendid task of the generation today wakening to its duty. These artists, weary of the "grand gesture" of romanticism, saddened by national defeat, incapable of understanding the meaning and grandeur of a civilization of the future, heralded by the noise and tumult of machinery, took refuge in the Past, in the mysticism of the Middle Ages.

Sar Peladan

They allowed themselves to be lulled to rest by the religion of their childhood, by all that it offered them in the shape of atmospheric distance and revery, seeking to find the true well-spring of this faith shrouded in the mists of passingcenturies, in order to drink forgetfulness of self, and of their incurable nostalgia, and to lose themselves voluptuously in the oblivion of its waters. Wagner, no doubt, had pointed out this road to them, one swallowed up in the ecstasy of Parsifal, and the sombre pessimism and despair of the Trilogy.

Poster for the first Rose+Croix Salon, 1892, designed by Carlos Schwabe.

Yet Parsifal passes beyond Christianity; it is the product, not of an unbalanced nervous system, but of creative thought whose agony is prompted by mysticism. Parsifal is an expression of the supreme desire for a Future which is the hope of our dreams. Wagner was born too soon to see this future, too soon to actually "think" it; yet toward it his whole work reaches out with desperate magnificence.

It was those destined to realize "beyond Wagner" whom Wagner himself would have given so much to reach. They are sure to come, and that ere long. . . .

The generation of French symbolists ranged itself under the aegis of Bayreuth. Peladan wrote his Le Fils des Étoiles, a Chaldean Wagneresque, for which Erik Satie composed preludes (one of them given at the great Metachorie performance in the Metropolitan Opera House, April 4, 1917, under the title Hymne au Soleil). And to this period also belong Sonneries de la RoseCroix (1892); Upsud, Christian ballet for one character (1892); Danses Gothiques (1893); Prelude de la porte heroïque du ciel (1894); La Messe des Pauvres (1895); and the Hymne au Drapeau, for Peladan's Le Prince de Byzance.

Here the monotonous alignment characteristic of the first works is somewhat broken. Satie continued to write outside the pale of tonality and rhythm: and this "atonality" is the great new thing of value which he gave music. These tonal combinations, most daring for that period, not only recall Debussy, but on occasion Stravinsky (as for instance the chords at the beginning of the second prelude to Le Fils des Étoiles). Side by side with them we find the greatest commonplaces and finally, to make incoherence still more confused, appear those improbable annotations which, thenceforth, more and more frequently companion Satie's music.

It is vain to look for a trace of meaning in them. Among Peladan's mystic symbols they have an aspect of paltriness which puts speculation to flight. Whom or what is he ridiculing? Is it Peladan? Is it mysticism?

In truth it seems as though Satie has already commenced to ridicule himself, and that his pretended religiosity is no more than a farce by which he allows himself to be snared. What is his motive? Might it not be mere impotence?

It is easy, in fact, when our thoughts are confronted with the great mysteries, when they are anguished and terrorized by their tragic meaning, it is easy to turn aside and make light of them —a jest accounts for everything. It holds a suggestion for superiority, of decided elegance. Yet, in most cases, it is no more than a facade, a masque which has nothing to conceal, the fear of a vain impotence reluctant to admit defeat, and which prefers theraillery that is no more than a subterfuge to the chances of combat.

The decadents and other neo-mystics have acknowledged that life has beaten them; that they are powerless. And they have adorned their psychic adynamy with beautiful dreams, with fair vices and elegancies. Erik Satie has sought salvation in ridicule. And from the pseudo-mystic he seemed to be at the beginning of his life, he soon became a mere mystifier.

The compositions he now writes are labeled with the most fantastic titles.

We have Pièces froides (1897); Morceaux en forme de poires (1903); Véritables préludes flasques, pour un chien (1912). In 1913 he composed Les Pantins dansent, played in his own orchestration at the Métachorie festival in Paris, in December; his Descriptions automatiques, Croquis et agaceries d'un gros bonhomme en bois, Chapitres tournès en tous sens, followed by numerous pieces of the same kind. More and more the "literary" program — strange, to say the least — which appeared in the compositions of the earlier Satie, ostentates itself between their measures. At times it extends without interruption throughout the piece.

Santiago Rusiñol - Portrait of Erik Satie Playing the Harmonium

One might be inclined to think that the composer had meant to write a musical recitation. Not at all: in one of his last compositions Satie even specifies that his prose should not be read while it is played.

Are these annotations, then, merely intended to enlighten the intelligence of the pianist? Should this music, perhaps, be read, not heard? Is it meant to appeal to the individual alone, and not, as in the case of all music, to the many? Does it address itself to a single mentality, and not to the sum total of intelligence? Does this music represent no more than a strictly individual pose, a clown's grimace before life's eternal verities? May this music, in short, be called music? Has ridicule any right to the name?

These numerous interrogation marks which Satie's compositions call forth lead us far beyond the mere personality of their author. The question takes on a wider scope and touches on the values of music itself. And first of all it compels us to exactly define the meaning and nature of irony.

Irony is essentially, and even in a unique manner, an intellectual fact (I use the term intelligence in its strict sense). And in a manner it stands for the bankruptcy of the intellect which, unable to pass beyond its own limitations and thrust back on nothingness, scoffs at its own and every other effort, and ridicules life, whose veritable and mystic essence it has been unable to penetrate. Irony is, in truth, the vitality of impotence. It is also, if one wishes, the triumph of pride over death, in the sense that the individual, refusing to perish, denies death as well as life, exalting himself in negation. For Irony is negation.

And since it is purely intellectual, it is, owing to this very fact, rigorously individualistic, for it is the intelligence which has shaped the idea of the individual. It is a negative and contemptuous attitude on the part of the individual toward life; a pose, be it brutal — as when it takes the form of sarcasm — be it elegant — when in the shape of delicate irony pure and simple — yet always, speaking in strictly human terms, unnatural and artificial.

For those to whom the individual is a godhead; those who regard existence as a defiance to nature, who are perpetually crying "No!" to Destiny, and who flatter themselves with the vain and arrogant illusion that they control her; for those who hold that the intellect is supreme, the enemy of instinct, disdainfully qualified as an animal trait; for those who drape themselves in their human, their purely human intellectuality, and as far as possible ignore that which lies beyond it, who renounce and mock it; for them irony is fitting, they may laugh their fill, and pride themselves in truth on the pride which is their idol, in that they are the only beings who may laugh, and glory in the very fact that they laugh at their own cosmic revolt.

Thus it is that every epoch, every agglomeration of beings where individualism dominates or exalts itself, where the individual stands for the ultimate expression of values, is also a focus of irony. There scoffers and caricaturists may be found in number.

And it leads to incessant disparagement, to the jocose verbosity which, seemingly inoffensive, saps all sustained effort, every great quest, devours and poisons all healthy vitality of striving out of which destiny is so largely evolved; from which spring those ardent cosmic forces, the torrents of energy whose synthesis hides the souls of races; where the future is born.

Paris thus came to be a centre for this sterile individualism, this mundane irony. Too many talents, too many intellects were drawn together by the irradiation of thought proceeding from this unique and monstrous city. And the many brains thus assembled, owing to the lack of a normal, cosmic development brought about by keeping in contact with the soil, in touch with the soul of their race, have denied each other in common, mutually devoured each other, in an enervating atmosphere of mockery and envy, glorifying their fanatic individualism, superexalted to the point of a mad search for originality at any price. Of this typically Parisian spirit, mocking, facetious, fond of mystification, destructive and in most cases incapable of production, beyond compare when it comes to disaggregating and dissolving all force, all power, with a smile, Erik Satie is the very incarnation.

He is a typical product of the beginning of this century, of this exhausted civilization which jeers in order not to look death in the face. And he is the buffoon, who cracks his punning jokes in increasing number, pushing them to extravagance, in order to make the neurotic beings who march past him laugh despite themselves, these luxurious adventurers who flock to shake off their thoughts in contemplation of his poverty.

But nature had gifted Satie with the musician's sense of hearing. And thus the latter carries over raillery into music, and writes "the music of irony," the name so aptly applied to it by Valentine de Saint-Point. In so doing he denatures music absolutely, and this artistic contradiction is plainly shown by the fact that he has recourse to the aid of the written word to express his raillery with precision, thus creating a hybrid ensemble which nolonger deserves the title of music.

Satie, an extreme individualist, writes for a few detached individuals, not for humanity at large, to him an object of derision.

Only the pianist — or the cultured musician — is able to appreciate his irony to the full; since they only are able to read and hear at the same time. And this musical impossibility is, nevertheless, quite capable of explanation; since irony, being an absolutely intellectual product, voices an appeal to the reader. Yet it cannot be termed music; since music is not intellectual in its essence.

Satie, wishing to express irony, has been unable to satisfy himself by employing purely musical means. In vain he has pushed the intellectualization of his music to its limits ; it did not suffice. He found it necessary to add a textual complement, to use words, since these alone are exact, and alone able to conform to the individualistic scheme.

In this way he has called into being an inchoate form for the sole use of a few musician "readers."

The fact is a good illustration of whither Satie's music tends, even though its contiguous prose were left out of account (which would be an unpardonable wrong, seeing that both evidently form a whole). The trend of Satie's music is toward intellectualism, exactness in narration and description; it tends toward language, used in its most strictly individual form, for purposes of raillery.

A savage intellectualism ; a particularism carried to the extreme, in which irony and farce are mingled; an entire absence of all that is beyond a strictly human comprehension; and, in consequence, positive artificiality — such are Erik Satie's characteristics, in particular during the past twenty years, since he matured. And all this is the exact opposite of music and of art.

For art has neither meaning nor value, unless as a synthetic expression of life as a whole! Now, our intellect, our individuality, is but one of the elements of life as a whole, and not the most important, an element which in no case may insist on a predominant place for itself. It is an element which is even less able to serve as a substitute for the whole, unless it be under penalty of becoming a monstrosity of radical unbalance, impossible to legitimate or admit; since the universe at all its points tends ever toward balance as regards scope and duration, nothing possessing value save in the degree that it approximates equilibrium.

For centuries man has been a vital monstruosity. Exalting his intellect, conceived as the supreme value of a mechanical universe — that of Descartes and Newton, a universe of cadavers and automats — glorifying his individuality, priding himself on a freedom which actually and in fact cannot exist in the individualistic domain, modern man, the man of science, represents a continual defiance of life, which his impotence, vanity and ignorance bid him deride.

Music, more than any other art, owing to its very nature, evades the individualistic scheme and the scope of its limitations. Music, an art of permanency, the direct expression of vital development in its essential continuity, has laid upon it the positive duty of rising above intellectualism, and above the individual, and in particular above the personality of the composer, whosoever he may be.

Beyond question the intellect has its part in music, as in every other art. The introduction of the intellectual element is necessary to the completeness of music; yet this element, an element of balance, may in no wise arrogate to itself a preponderating position, especially since, as in the case of the real Satie of the last phase, the resultant offspring is a bastard, and from the standpoint of art, nonsense.

Since irony is strictly an intellectual individualist factor, any such thing as the "music of irony" must, to be consistent, be considered nonsense. There can no more be such a thing as "ironic music" than there can fail to be rational, that is to say genuine music, which has an absolute and enduring value.

Erik Satie's pieces have an individual and an intellectual value; they have no really musical value. Yet one thing is beyond question, and that is Satie's extreme originality. Yet may this be said to have a vital artistic value? Evidently not. In Art — as in Life itself, where results alone are valid, and effort is negligible — the work alone counts; the artist does not. And his work is not truly inspired unless it expresses the immortal soul of man.

Now this soul does not change through the ages; judgments, individualities only are modified in accord with new means of expression and action. So that the work of genius is never original, since at bottom that which is new in it — its forms — is that which is least important. A work that is all originality is fatally superficial: it is the mere expression of individual peculiarity, often consciously insisted upon, on the part of impotence.

Satie's work represents originality only, like the major part of the artistic tentatives of this terminal epoch of our civilization.

It is full of strange individual traits, it surpasses itself in exploiting their particularisms, formulating a doctrine and an art upon their physiological anomalies or, often the outcome of a craving for novelty at any price, continually attempting to do the opposite of that which is being done. In Erik Satie's pieces there is only —Erik Satie: the really human element is missing.

Let us once more repeat that particularism is incompatible with art, andespecially so with music, the most impersonal, the most soul-inspired of the arts. Hence, Erik Satie's works do not truly belong to Art in the veritable sense of the word; they do not belong to the great Art of humanity.

Yet if we leave this field, and take the historic point of view, if we study the evolution of the language of music, of form, of expressional mediums; if from the human point of view we pass to the musicological, then we cannot but recognize the important part played by Erik Satie.

He has been, without any question, a precursor.

His Sarabandes anticipated those of Debussy by several years, and beyond doubt Satie helped to liberate Debussy from the old scholastic rules, and was able to act in his case as the small separating cause so often needed to set great issues acting.

Yet, service in this way is valuable only from the individualistic point of view; in reality it has but little meaning. It is time, in truth, that men begin to appreciate works themselves and not what underlies them. It is time that the shocking impudence of these posthumous biographical revelations anent great men come to an end. There are no great men. There are only great works! The great works are not the work of an individual.

They represent the expression of an immense synthesis of forces materialized through the medium of an artist. Yet what matters the medium, this cosmic transformer? The artist plays the part of a phonograph. There are good phonographs and poor ones. Yet does that fact really affect the absolute value of the music registered? Of what importance is the protagonist, if hundreds of forces collaborate in his work? Of what importance is ever the individual? And is it not decidedly vain to investigate the paternity of a work or of an idea, when the work in itself is the only thing that counts?

Finally, as between the Fils de Ètoile and Pélleas et Melisande, there is the difference between the expression of a strange individuality and the tragedy of undying humanity. And what gives Debussy his value is not his harmonic processes; it is the fact that he has a great conscient soul, the synthesis of multitudes that are not conscient, a synthesis whose realization is a great work which will live.

Satie has found numerous ways and means before him unknown. Debussy has availed himself of some, Ravel of others. They are beyond question those which are least interesting. Satie, no doubt, draws from the fountainhead of many things, but it is the source of all that there is in the way of extremest originality, of singularity, of extravagance in French music of the time being; of all that there is in it which is trifling, finical, artificial. Satie is a well-spring; but one whose waters are poison.

The Protagonist, in truth, does not amount to much beside the Realizer — since all values must be measured according to the intenseness of consciousness in eternity; and the germ is as nothing beside the thought of humanity, that same germ which, nevertheless, contained its power. Yet — if to be the precursor of a formidable achievement is of undeniable worth, what may truly be said of the initiator of trends which are unhealthy and unfruitful?

And that is what Erik Satie has always been; and what he still is. Let us admit then that he may be of great interest to the musicologist, the historian; let us concede him the eminent place due him in the evolution of contemporary French music.

Yet, if we are to consider his works from the sole point of view justified by Art, the point of view of the sum total of humanity that in them is, not even of super-humanity — since Art, like Life, should ever strive toward a more intense consciousness — we are forced to state that these works of Satie have only an infinitely limited value, musically almost null. For this will always be the case in music which, disdaining man's inmost soul, denying life, is no more than the particularisms expression of a narrow and distorted individualism, based solely on intellect.

(Translated by Frederick H. Marteni)

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World

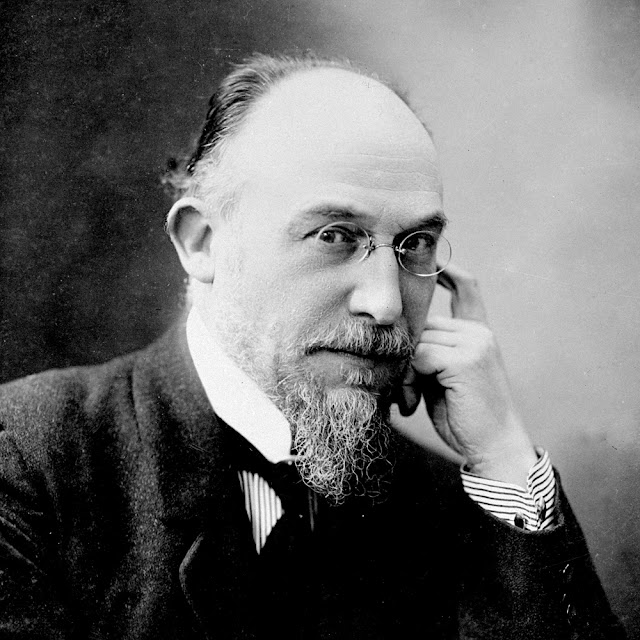

ERIK SATIE

In America, Erik Satie has until recently been known as the man who calls his music by funny names and who further adds ludicrous directions to the performer of his litttle piano pieces. Even in Paris the bearded and bespectacled founder of the modern French impressionistic school was, for a long time, only given credit for the composition of a few music-hall pieces, but his friends, Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy, have let it be known what they owe to him.

Satie was born in 1866. Twenty years later he was composing music in Paris, music wholly out of keeping with his period.

Satie, either by direct inspiration, through imitation, began to ignore the modern scale system from the beginning. It is significant, for example, that he wrote music in the whole-tone scale before Debussy ever thought of doing so. That Satie furnished one of the necessary links between the music of the past and the music of the future, only a reactionary critic would attempt to deny.

Satie's music has charm of its own which may not penetrate into your consciousness at once but, in the end, quite takes possession of you.

From the program of Eva Gauthier's Song Recital,

New York, March 12, 1919, of modern French and British composers.

MORE in PREPARED GUITAR

The Music of Marcel Duchamp (April 04, 2016)

The Liberation of Sound by Edgard Varese (March 11, 2016)

Sound Aesthetics Iannis Xenakis Films (January 14, 2016)

Morton Feldman and Iannis Xenakis - In conversation (January 8, 2016)

Sound Aesthetics: Xenakis (January 7, 2016)

Sound Aesthetics Christian Wolff on Feldman (October 23, 2015)

Pinhas Deleuze Sound language (January 21, 2016)

John Cage and David Tudor - Music in the Technological Age (September 15, 2015)

John Cage and Morton Feldman In Conversation (September 8, 2015)

4'33'' Cage for guitar by Revoc (July 10, 2015)

John Cage: An Autobiographical Statement (May 22, 2015)

Angle(s) VI John Cage (April 30, 2015)

Morton Feldman (March 16, 2015)

Morton Feldman and painting (October 3, 2014)